Cracking a DLL, Part 1

Preface

At the last company meeting, it was revealed that the resident company "cr4x0r" had removed a bomb date from a DLL used in an upcoming product.

The company meeting was a bit light on technical detail, so (thanks to Jacob's prompting) I'm going to blog how it was done for any interested parties.

Background and Motivation

The specialised search engine is implemented by a library named X. Somehow, someone found out that X.dll would stop working after 1 April 2004.

Since this DLL is the core of the product, it was essential to modify it so it would continue to work. Not having the source code for the DLL, this was a non-trivial operation.

Possible Approaches

All that we have to work with is the machine code output from the Delphi compiler. Somewhere in the DLL must be a check of the current time against a bomb date. Maybe the bomb date is hard-coded in the DLL, maybe it is in the datafiles. Maybe the bomb date is the actual date, maybe it's the number of 100-nanosecond intervals since 1 Jan 1601. Searching for the bomb date itself would not be profitable; however, there must be some code with the following structure:

if (CurrentDate < BombDate) then

proceed

else

crash

There were two ways to go about finding this code (or the assembly language representation of it) in the DLL:

- Bottom-up — find the code that gets the current time and examine the surrounding code in hopes of finding the check.

- Top-down — debug the program one line at a time, with the system clock set before and after the bomb date, looking for differences in program flow (i.e., finding the if/else statement).

I elected to pursue a bottom-up approach first; it seemed that this would require less assembly language code to be examined.

Bottom-up Approach

Finding the Code That Gets the Current Time

At some point, X.dll has to ask the operating system what the current time is. Windows provides the functions

GetSystemTime, GetSystemTimeAsFileTime and GetLocalTime for this purpose. If we were

lucky, we would find a direct call to one of these functions in X.dll. If we were unlucky, X would descramble

the desired function name at run time (so that you couldn't find the name in the binary) and dynamically link to kernel32.dll

in order to call the function.

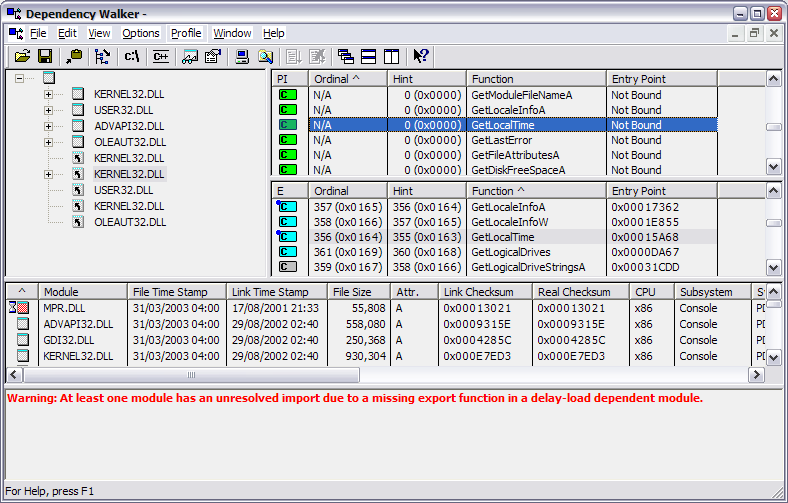

I fired up Dependency Walker and, sure enough, X.dll contained a reference to GetLocalTime (in kernel32.dll).

(This reference is stored so the OS loader can fix up addresses when the DLL is loaded. Because DLLs can be loaded at different addresses in memory (and because

kernel32.dll is different in different versions of Windows), the actual location of

the GetLocalTime function can't be hardcoded in X.dll. Instead, a relocation table is used.

The relocation table basically looks like this (well, in pseudo-code):

...

void GetLocalTimeStub(LPSYSTEMTIME lpSystemTime) { goto GetLocalTime; }

void GetSystemTimeStub(LPSYSTEMTIME lpSystemTime) { goto GetSystemTime; }

...

The DLL's compiled code calls the GetLocalTimeStub stub function instead of the real kernel32.dll function.

At load time, the OS walks the relocation table and fills in the actual address of the functions in other DLLs. Since those

DLLs have already been loaded into memory, the real addresses of the functions are known.)

I suddenly realised that I didn't know how to read relocation tables. I wanted to put a breakpoint on

GetLocalTimeStub so that I could debug the program at the point where it called this function, but I didn't

know where this function was located in X.dll. However, Dependency Walker told me that

GetLocalTime is located at an offset of 0x15A68 in kernel32.dll. Combine that with

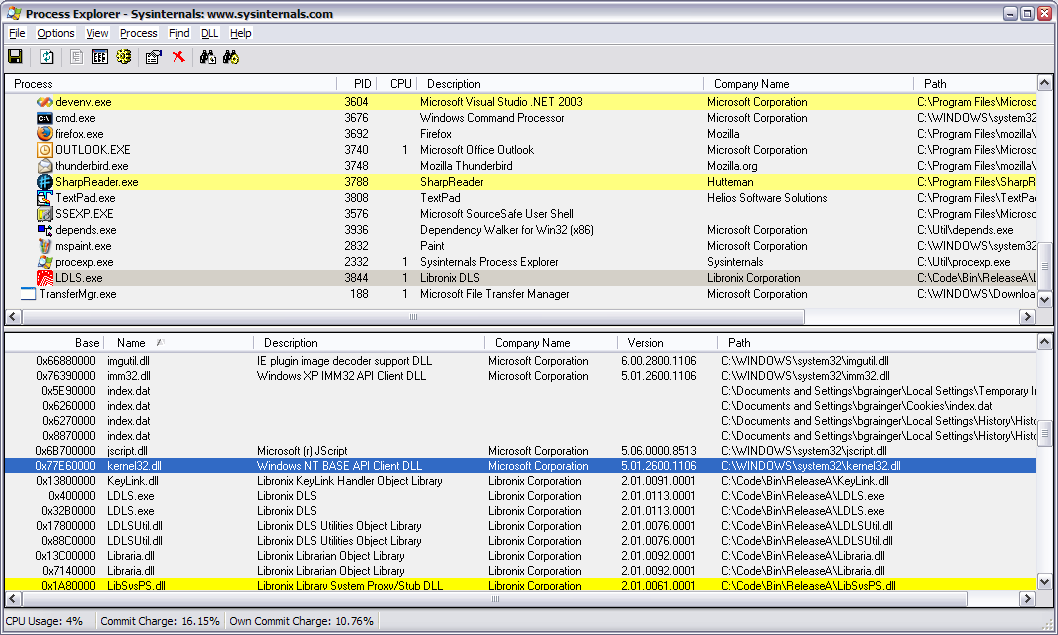

Process Explorer telling me that LDLS.exe

loaded kernel32.dll at 0x77E60000 and we know that the code for GetLocalTime is located at

0x77E75A68.

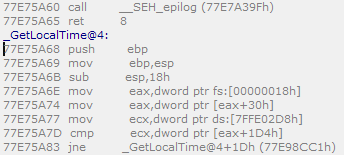

In the debugger, it's as simple as pulling up the Disassembly window, entering that address in the address box, and setting a breakpoint on that byte of code. (With debugging symbols installed, the debugger will even helpfully put "_GetLocalTime@4:" above that line of assembly language.)

Analysing the Code That Gets the Current Time

We now invoked the CreateData function in X.dll. The debugger immediately stopped on a call

to GetLocalTime. The call stack window revealed that we were four functions deep inside X.dll.

The function that was calling GetLocalTime was the first thing to investigate. It allocated 32 bytes on the stack (the

size of a SYSTEMTIME struct), passed the address of that struct to GetLocalTime, then called another function with

the st.wYear, st.wMonth, and st.wDay values. This in turn called a third function which appeared to check the validity

of the date. It ensured that the year was between 1 and 9999, that the month was between 1 and 12, and that the

day of the month was between 1 and the maximum number of days in that month (having already called a fourth

function to determine if the current year was a leap year). Since we just got the date from the OS, it seemed unlikely

that it would be invalid, but it can't hurt to check, I guess. It then calculated (based on the year/month/day values) the number

of days since 1 Jan 1900 (just making a guess at this epoch start date, actually, but it's probably somewhere around that time)

and converted that to a floating point number. A similar validity-checking procedure was carried out with the hour,

minute, and second values, and then they were converted to a fraction between 0 and 1 and added to that floating point number. The

program then immediately converted that floating point number to an integer, stripping off the fractional part.

We continued debugging the code, making notes on what we thought the program was currently doing, until

we realised that I was hopelessly lost. We hadn't written down the execution path of the program in great detail, and

I didn't know where I was in the program. The date check might already have been done. Or the date

might just have been stored in memory, and the check was going to be performed elsewhere. At that moment, D.F. called

and invited us to see a movie. It seemed like we had reached a good stopping place.

Continue reading Part 2.